RICHMOND, Va. (WRIC) — In two weeks, a group of Richmonders plans to gather in front of the Old Richmond Community Hospital.

They’ll keep sharing the history of the building and of those who worked there during segregation. They’ll try to do what impassioned groups have done before — stop history from being demolished and influence how it’s saved.

Two years ago, activists protested the potential demolition of Second Baptist Church in Monroe Ward to create a parking lot. In 2011, the Leigh Street Armory was saved from a fate of demolition by neglect thanks to years of behind-the-scenes negotiations. And five years before that, the Robinson Theater started its journey of revitalization.

In this case, its story of new beginnings began with two couples who previously had no connection to the building or neighborhood at all.

Restoring a community connection

Two couples — the Bennetts and Thalers — brought life back into the Robinson Theater which, for most of neighbor Wanda Canada’s life, was crumbling. During these early days of busing, rezoning handed her a weaving path to school through adjacent neighborhoods, past the Robinson.

“I would imagine — ‘I wish I had enough money to bring that back to life,’” Canada recalled. “‘That is beautiful architecture. Why doesn’t someone see it?’”

The theater’s current owners, the Bennetts and the Thalers, said they eventually did see the potential in it. They said it was early discussions with community members, as well as Mitch Bennett’s research, that revealed how they wanted to approach it.

“It was people telling us what it meant,” Debbie Bennett said. “Mitch [Bennett] started digging a little deeper into what it had been and there was a turning point where we said, ‘Okay, well if that’s what it had been to the community, then that’s what it needs to be again.’”

The Robinson’s history traces back to its opening in 1937, when its completion was seen as the final marker of the neighborhood’s transformation into a middle-class black neighborhood. It was named after Richmond native and Broadway sensation Bill “Bojangles” Robinson.

But after decades as a hotspot for community gatherings and celebrity sightings, it became a pool hall, then fell into disrepair until the owners saved it with meticulous attention to historic detail. It was a painstaking and costly process that took multiple years.

“When we bought the building, there was a giant disco ball hanging from the ceiling,” Debbie Bennett said. “They closed the door, took the marquee down and, for 20 years, it just sat vacant on that corner.”

The cost, Michael Thaler said, ended up being seven times more than the initial cost before they determined a historical restoration was best for the building and the surrounding community.

“The building itself was the same cost as building a replica of that marquee and putting it on the Robinson Theater,” Debbie Bennett said. “It was a huge expense to do that, but we knew it had to be done because it wouldn’t look the same if it wasn’t.”

“The tagline is, ‘We’re for the neighborhood,’” Mitch Bennett said. “And that really has held all these years from early on. Just being a community arts center for the neighborhood.”

The cost and work underscore the amount of effort required to save these buildings from what Richmond historian Selden Richardson calls “demolition by neglect”.

Across town in another historically thriving, middle-class black neighborhood is one example of a building Richardson nearly suffered that fate. But instead, like the Robinson Theater, the Leigh Street Armory has had a similar story of rebirth.

Rebuilt By Blacks

“The upper portions of it had somewhat collapsed and were in disrepair,” said architect Burt Pinnock as he pointed out the parts of the building that required the most attention when the firm he used to own, BAM Architects, was hired to lead the Leigh Street Armory’s renovations, which officially began in 2014.

The Leigh Street Armory was originally constructed in 1895 for Richmond’s first African-American regiment, the First Battalion Virginia Volunteers Infantry. It was later used as temporary housing, a recreation center for African-American troops during World War II and a school until the 1950s.

For decades, it seemed a devastating fire in the mid-1980s had sealed its fate.

“It stood like that for a long time until at least the city stabilized it, got a roof on it so it doesn’t just crumble,” Pinnock said. “But when we started the project, it needed a lot of love.”

His firm worked with a structural engineer and the Department of Historic Resources to figure out how to ensure the renovations would withstand the test of time.

“It was a little daunting,” Pinnock said. “I was a small, minority-owned firm with a very huge responsibility. But I want to say we stepped up.” With a laugh, he added, “We can ask them inside.”

Inside is the Virginia Museum of Black History and Culture which spearheaded renovations to the armory , which still stands there today.

Pinnock said the difficulty in revitalizing long-neglected buildings like the armory is figuring out how they can best serve the often long-neglected communities around them.

“So actually trying to work with the client, working with the community members who gave their time and effort, to understand how do we position this building to truly serve the community?” Pinnock said, explaining how he approached that problem.

Pinnock shared how daunting yet rewarding it was to work on such a project.

“To be able to participate in such significant work that is built for Blacks, built by Blacks, meant for Blacks?” Pinnock asked aloud. “I can’t … It’s hard to put into words how overwhelming that is sometimes, but I’m grateful.”

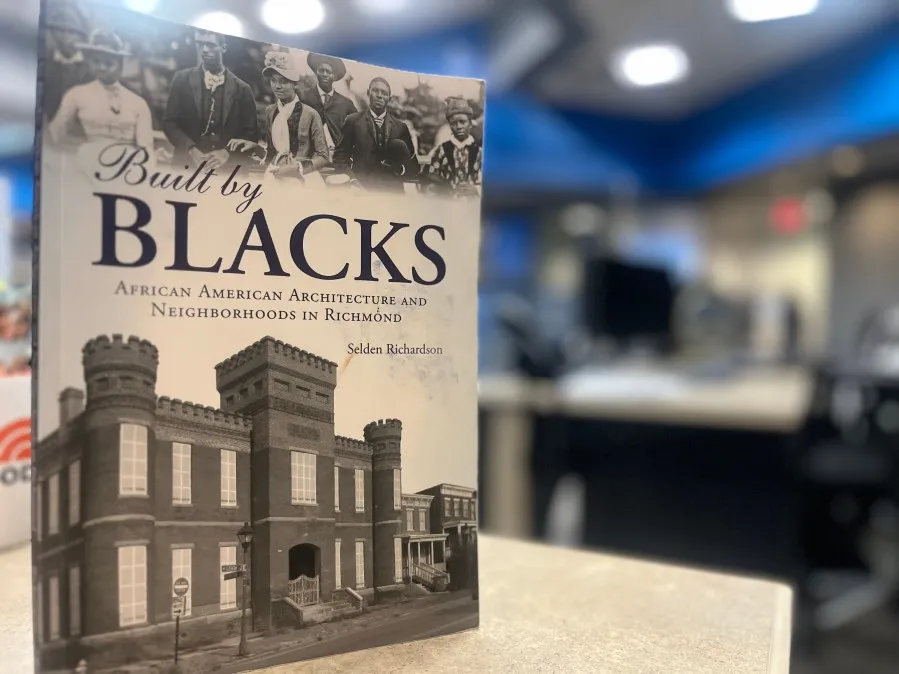

“Built by Blacks” is not only a concept imbuing some of these historic buildings with pride.

It’s also the title of Richmond historian Selden Richardson’s book, which details the history of the city’s buildings built for and by Black Richmonders.

“It started really as a preservation tool,” Richardson said of why he wrote the book. “At the time, it was the creation of a group called the ‘Alliance to Conserve Old Richmond Neighborhoods.’ And we felt that if we could bring more knowledge of these threatened and fragile areas of Richmond, we might bring more appreciation of them. And with more appreciation, you’d find less demolition and really people caring about them more than they did.”

Avoiding demolition by neglecting what remains

“You have the buildings that have been saved and will always be intact, like the armory,” Richardson said. “You have some that have disappeared entirely, like the Eggleston Hotel.”

The armory’s fate wasn’t always as certain as it now seems. At one point, it seemed as destined to be bulldozed into rubble as the Eggleston Hotel was.

Both buildings, Richardson said, initially faced the possibility of “demolition by neglect” because no one cared enough to save them after fires, structural damage and decades of abandonment.

The armory was saved. The Eggleston was replaced with another building and a state marker later erected to honor its history.

Jacqueline Finney Mullins, The Valentine)

Diagonal from where the Eggleston once sat, other icons of Black architectural history — the Hippodrome and the W.L. Taylor Mansion — still stand. Pinnock, in his previous firm, helped design the way to save them both.

He and other Black architects, along with Black property owners have to save as many as they can. Often, they choose to honor some elements of the building’s original purpose when they do.

They said this mission is even more critical now, amid gentrification and newfound city priorities that can either complement or compete with a community desire to celebrate and preserve Richmond’s Black history.