After Curtis Brown’s 30-year tenure with Merrill as a financial advisor who became a branch manager and a high-ranking executive, friends and colleagues urged him to tell his story in a book.

The thought of people “either currently in the business or contemplating” a career in wealth management convinced Brown, 72, that he should write a memoir that could help toward “inspiring others to want to get into our industry,” he said in an interview.

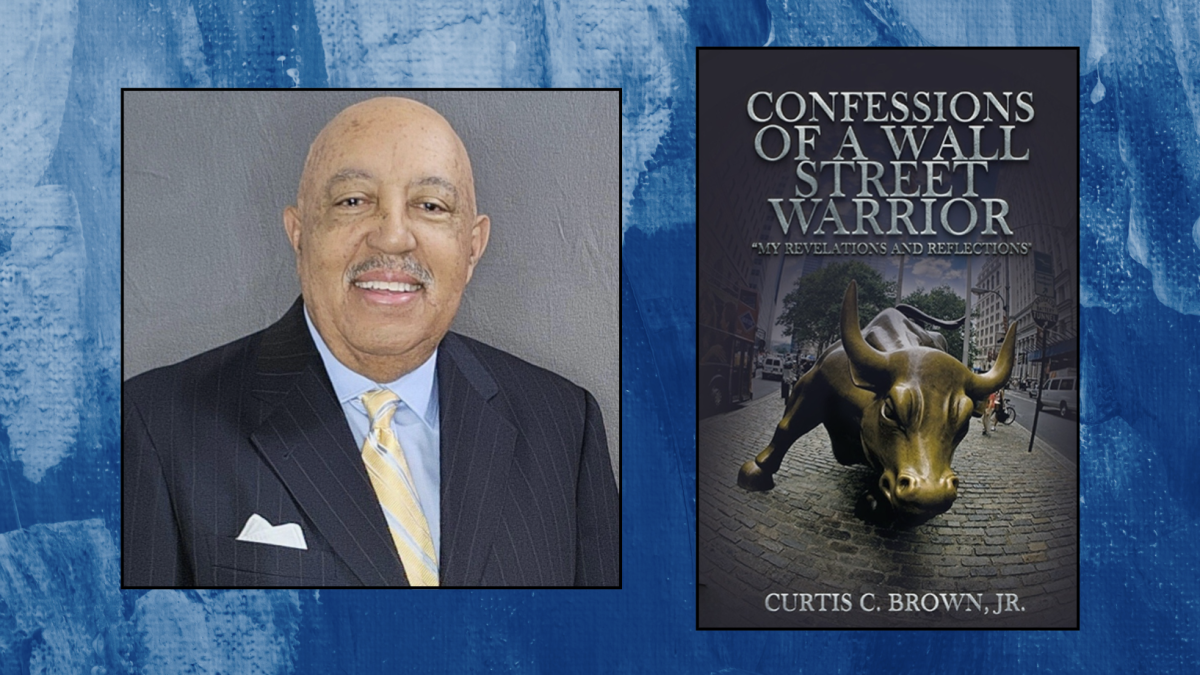

Curtis Brown

“You have to take responsibility for your life, for your career, and you need to be thinking about your own personal journey. You need to have an awareness that everything’s not smooth sailing,” Brown said. “There are going to be moral dilemmas that you face.”

The resulting book, “,” shares the tale of an Army brat and martial arts expert who . Brown joined Merrill in 1978 and worked his way up to being regional managing director, national sales manager and assistant to the chairman and president. Brown — now a coach to advisors and executives as a — provides a chronicle of how the profession has changed over time and the high stakes of recruiting fights for top talent, among other lessons for planners and aspiring ones.

“No. 1, they are in very, very good careers that can help a lot of people,” Brown said. “I think the operative word is you really are selling dreams, hopes and aspirations. You’re not just selling products. You’re having people latch onto a dream.”

Brown formed an early impression on Keith Henry, a regional director at , at a reception in 1986 honoring Brown as the first Black branch manager in Merrill’s history, Henry noted in an email. Brown “always made himself accessible and never forgot where he came from” regardless of his position in the corporate pecking order, and he “mentored and opened doors for the future generation of Black leaders,” Henry said.

“He had an impressive presence,” Henry said. “I remember speaking with him and thinking to myself, I want to be like him one day. Then, fast-forward 10 years later, I was nominated to join the training program to become a branch manager. And guess who became my mentor? Curtis Brown. Curtis had a profound impact on how I think of myself. He helped me build my confidence, technical knowledge and leadership skills. And he helped me overcome self-doubt. I remember him saying to me, ‘By the time you walk into that room as a branch manager, I’m going to make sure that you’re ready.'”

Many advisors entering the profession today — a field with a business imperative — don’t feel that same bond of mentorship from their managers, according to Brown.

“When I look back on my career, culture was the tie that bound people to an organization. Managers were like coaches. They took you under their wing. They were responsible for your development,” he said. “Now there are fragmented cultures. Managers have been taken away from the role of being developers of people, and so from a loyalty perspective I think financial advisors may see that as, ‘Hey, it’s open season, I alone am responsible for my career and my career growth.'”

However, Brown certainly accepted that responsibility for his own path, writing that he “was rejected by every firm I applied to” in San Diego and Los Angeles before he got a “glimmer of hope when Merrill Lynch called me back” about a position in the firm’s San Francisco office. The company had placed an add in The Wall Street Journal with a picture of “a neatly attired African American male in a business suit” and a headline reading, “I belong on Wall Street, especially with Merrill Lynch.” Brown found success in building a book of 400 clients despite encountering “the look of surprise when a white person sees you for the first time” and a “dynamic tension navigating between the Black world and the white world,” he writes.

Taking a cue from the HBO series “True Blood,” Brown said that his adopted method for responding to that latter challenge, “shapeshifting,” refers to the need for many Black professionals in the corporate world to do two jobs at once: “one was the job that you’re hired to do and be good at that” and the other being to “change people’s perception about who you are.”

One aspect came with gaining memberships to country clubs and training to be a golfer. In general, it revolved around figuring out “how to adapt or assimilate into this new culture of Wall Street,” he said.

“It takes energy to behave in this manner and, at times, is quite exhausting,” Brown writes. “It was stressful for me to be in the dynamic tension of both worlds, one Black and one white, and I was determined not to let it bring down the inner warrior in me. I would not wear my frustration on my shirt sleeves.”

Curtis Brown

Brown also accepted new assignments requiring that he and his wife Pat move their family, including a position in charge of a complex of four Merrill offices in New Jersey and New York that he took in 1999. In that role, he quickly learned about the importance of recruiting advisors. The .

“I felt as if this war for talent was indeed an actual war,” Brown writes. “Each firm was fighting for market share and market dominance. If you were a leader and you didn’t recruit you wouldn’t get paid well and miss promotional opportunities in the future. I had no choice; I was being measured and the lack of recruiting could potentially affect my performance negatively as a leader. Over the next three years I grew the complex from a base of 50 financial advisors to 85 in one year. By the second year we had grown from a base of 85 to over one hundred and by the third year we had over 135 financial advisors.”

In relating the trajectory of his career and life afterward, Brown writes about other industry-focused topics like the financial crisis of 2008 and run-ins with regulators. He also covers more universal subjects, such as the wisdom he learned from his Vietnam veteran father, how martial arts boosted his professional achievements, the experience of losing Pat to cancer and surviving his own heart attack and bout with cancer.

The book closes with 14 takeaways for readers. People who have come to know Brown along the way have gleaned some of that knowledge already.

“Curtis told me to be 10 times more confident than I really was,” Henry said. “He always stressed to me that you’ve got to believe in yourself. Throughout your career, you’ll come across doubters. And it’s going to be 10 of them for one of you. He also taught me to be present in the moment and let go of the baggage of the past, which can hold you back if you’re not careful. I think this advice can be helpful to people with so many different experiences as they are advancing their career. Lastly, Curtis would say to always show up for the people around you. I still live by this principle to this day, and I think it’s important for managers, and future managers, to keep in mind.”

Over his industry tenure, the profession and career path shifted to planning and ensemble teams from how it looked in “my era,” Brown told Financial Planning.

“We were all sole practitioners. We were stockbrokers then,” he said. “The teams have gotten so large in terms of assets and clients that a lot of the coaching is about, how do you manage the process, how do you create a concierge practice creating a level of service that clients expect from you, and how do you manage your practice like a business.”