OGDEN, Utah –This week marked 50 years since one of the most brutal crimes in Utah’s history: the “Hi-Fi murders” in Ogden.

On April 22, 1974, three people were murdered and two others were tortured in the Hi-Fi electronics shop on Washington Boulevard. The sheriff at the time described the crime as the “worst mass murder” he had ever heard of in the northern Utah town.

Sarah Langsdon, the head of special collections at Weber State University, who works to document the history of the local area, said that the crime changed life for decades in Ogden, particularly in race relations.

“There was a lot of outrage,” Langsdon said, explaining that the three men convicted in the crime were Black and the victims were white.

Because investigators thought more men might have been involved in the crime, this created a sense of suspicion in town. Not only did parents not let children go downtown, there were also incidents of racial harassment.

“Ogden had always had some racial tension, being segregated and things like that, but this just kicked it up a whole other notch, because people were really afraid,” Langsdon said.

The crime

On the night of April, 22, 1974, Dale Selby Pierre and William Andrews entered the Hi-Fi Shop at closing time while Keith Roberts, the getaway driver, waited outside.

The three came from the nearby to rob the downtown store, eventually making off with $24,000 worth of audio equipment.

Inside the store were two young workers: 18-year-old Michelle Ansley and 20-year-old Stanley Walker. The robbers quickly took them hostage.

Not long after, 16-year-old Cortney Naisbitt, who went to the store to talk with Walker, was also tied up and brought to the basement.

Because Walker didn’t return home, his father, 43-year-old Orren Walker, went to the store to look for him. Similarly, 52-year-old Carol Naisbit went to Hi-Fi, looking for her son.

Pierre and Andrews brought all five hostages to the basement, where they were tortured and made to drink liquid Drano, a cleaning solvent. When this failed to kill them, Pierre shot each of them in the head. He raped Ansley before shooting her.

Ansley, Carol Naisbit, and Stanley Walker were killed.

George Throckmorton, a former forensic specialist at the police department who was one of the first on the scene, found one of the two survivors, Orren Walker, walking around. He had suffered multiple gunshot wounds, and a pen had need stomped into his ear.

The other survivor was Cortney Naisbitt. He also suffered life-altering injuries.

“We found out the grisly details,” Throckmorton

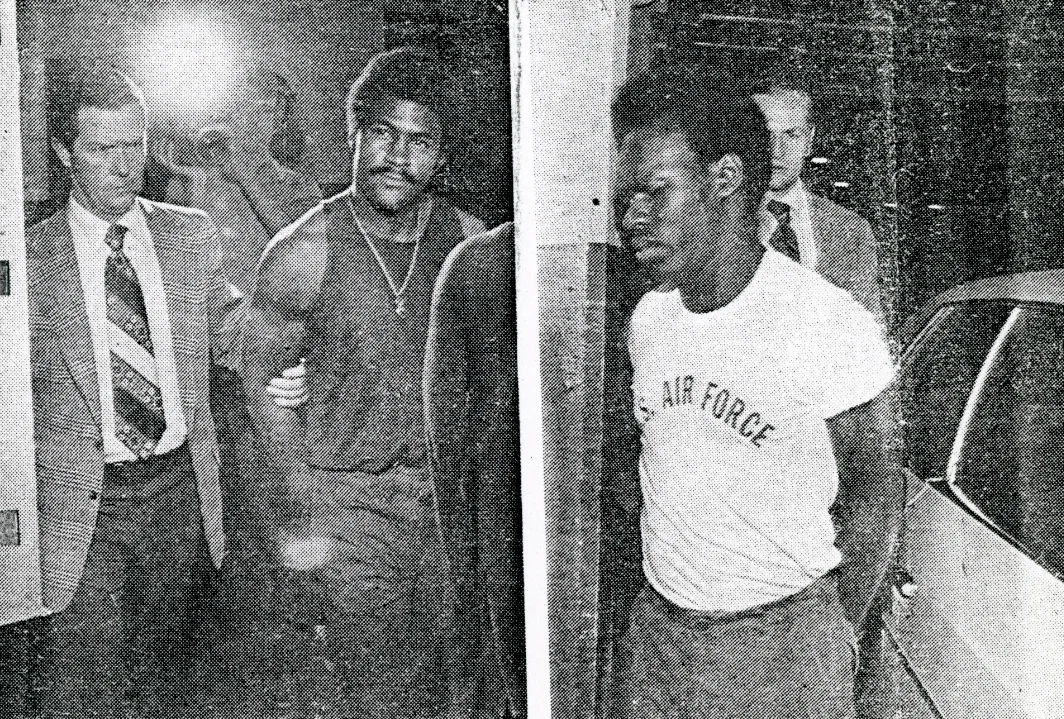

That night, the perpetrators got away. Two days later, however, a tip led detectives to Hill Air Force Base, where personal items belonging to the victims were found in a dumpster. Pierre was stationed at the base, and he was already a suspect in another murder.

While searching the barracks, Throckmorton discovered something hidden under the carpet. It was a lease agreement for a storage unit roughly a block from the Hi-Fi Shop. Pierre had signed it.

“I said ‘bingo, we’ve got him.’” Throckmorton said.

The storage unit was filled with audio equipment stolen from the store.

Death penalty

Pierre, Andrews and Roberts were tried together, and Orren Walker provided key testimony. Pierre and Andrews were convicted of first-degree murder and robbery. Both were sentenced to the death penalty.

Roberts, who stayed in the getaway van, was only convicted of robbery. He served 13 years in prison.

While behind bars, Pierre changed his name. He was executed by lethal injection in 1987. Andrews faced the same death in 1992, after 18 years of appeals. He claimed the death penalty unfairly targeted Black Americans.

“There are numerous instances that came after me that were perpetrated by white people, and in some cases, a lot of cases, first-degree murder wasn’t even asked for and why not?” he said in an interview before his death.

Black Americans and many Utahns supported a commutation of Andrew’s death sentence, as he didn’t pull the trigger. The NAACP and Amnesty International worked on the appeals.

The heightened racial tension in Ogden dissipated after Pierre and Andrews were executed, Langsdon said. She explained that the years of legal tussle kept the case at the forefront of people’s lives.

But fifty years later, even as the case is still in living memory, the Hi-Fi murders are fading in public consciousness.

“It’s just not talked about anymore,” Langsdon said. “Especially the younger generations, they just don’t know about it.”