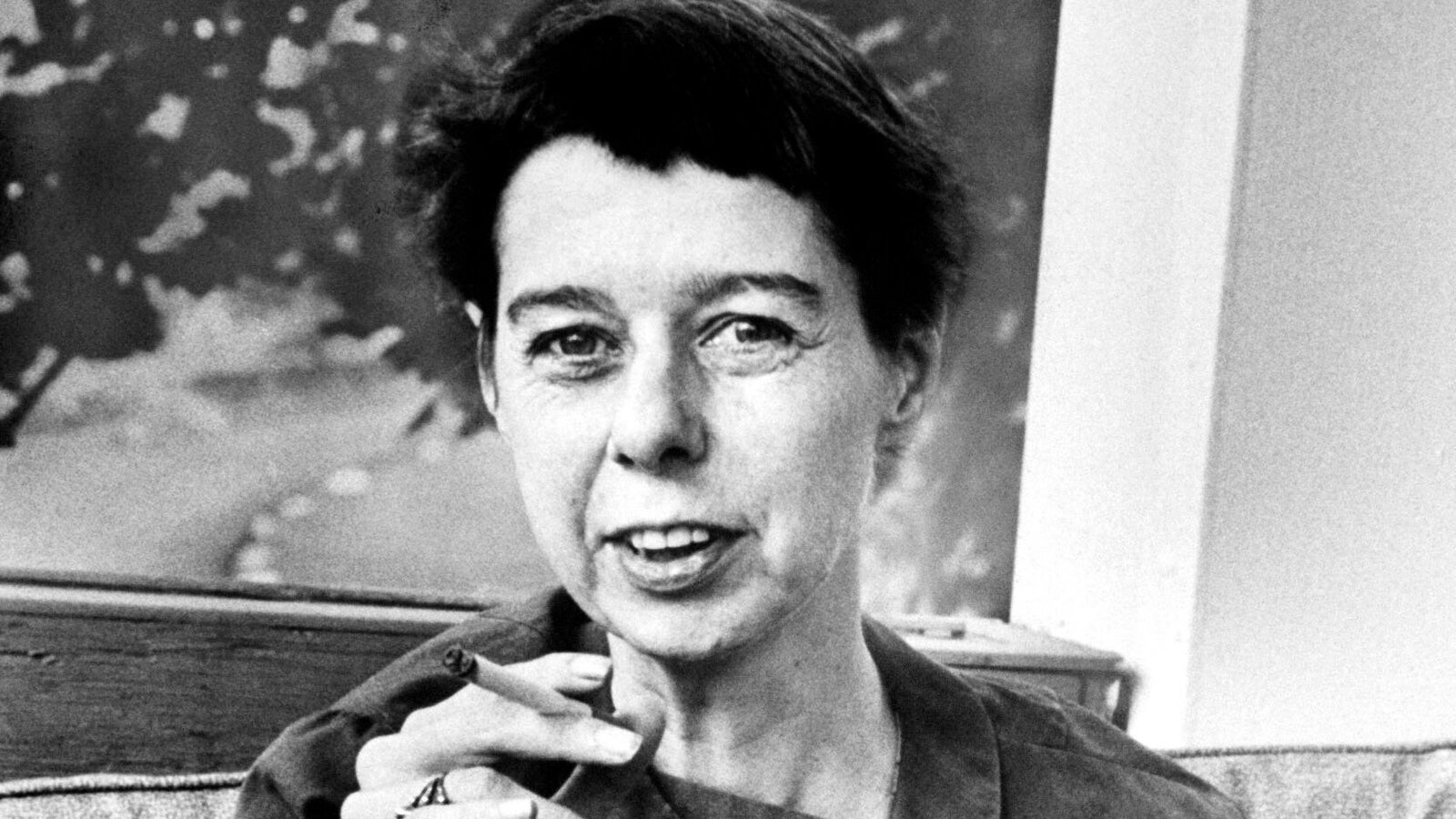

A recent biography delves into the intricate romantic life, distinguished career, and exceptional talents of a prominent American author.

“CARSON MCCULLERS: A LIFE” by Mary V. Dearborn

In her latest work, “Carson McCullers: A Life,” Mary V. Dearborn presents the most comprehensive biography of this significant American writer in more than twenty years. The book is crafted with precision and expertise, reminiscent of a well-built structure using sturdy pine and quality plaster. Dearborn’s approach is objective and meticulously researched, creating an intense reading experience as it delves into the harsh realities of McCullers’s life.

Dearborn faces the challenge of living up to the renowned biography by Virginia Spencer Carr, a masterpiece in the genre known for its dense narrative filled with intricate details, nuanced perspectives, profound humanity, and a touch of enchantment.

A notable difference lies in the opening passages of the two biographies. Dearborn begins with the lines:

Carson McCullers titled one of her early, more autobiographical stories “Wunderkind.” She embodied such a child — a double-edged sword, as is often the case with exceptionally gifted children.

In contrast, Carr captivates readers from the start with a vivid scene:

“You know what, Helen,” said the tall girl from Georgia, “let’s skip the cotton candy and hot dogs this time and save our money for the Rubber Man and all the sideshows. The Pin Head, the Cigarette Man, the Lady with the Lizard Skin… I want to see them all.”

This difference in style carries through the extensive narratives. Dearborn’s writing is concise, resembling a clinical setting or a museum display, presenting McCullers’s life as if in a well-lit exhibition. Carr, on the other hand, takes a more shadowy, ground-level approach, evoking settings like nightclubs or the back seat of a moving car. With Carr, readers feel immersed in McCullers’s life, catching glimpses of peripheral details as if in real-time.

Despite these stylistic variances, “Carson McCullers: A Life” stands as a significant contribution to McCullers’s literary heritage. It expands upon Carr’s groundwork by incorporating newly discovered materials such as letters, journals, and intriguing transcripts of McCullers’s psychiatric sessions in her later years with the female doctor who eventually became her partner and confidante.

Following the publication of McCullers’s complete works by the Library of America seven years ago, there has been a renewed interest in her body of work, particularly in novels like “The Heart is a Lonely Hunter” (1940) and “The Member of the Wedding” (1946), as well as the collection of short stories “The Ballad of the Sad Café” (1951).

McCullers’s skillful portrayal of outcasts and societal outsiders, along with her exploration of taboo topics such as mental health, addiction, and unconventional relationships, has garnered well-deserved recognition. Joyce Carol Oates aptly observed that “McCullers seemed to have identified with whatever is transgressive in the human psyche, viewing it as the very essence of desire.” While Dearborn touches on these themes, her primary focus remains on narrating the life story, with less emphasis on the literary works.