One of Saturn’s 146 moons is at the center of newly energized interest in the search for life in space.

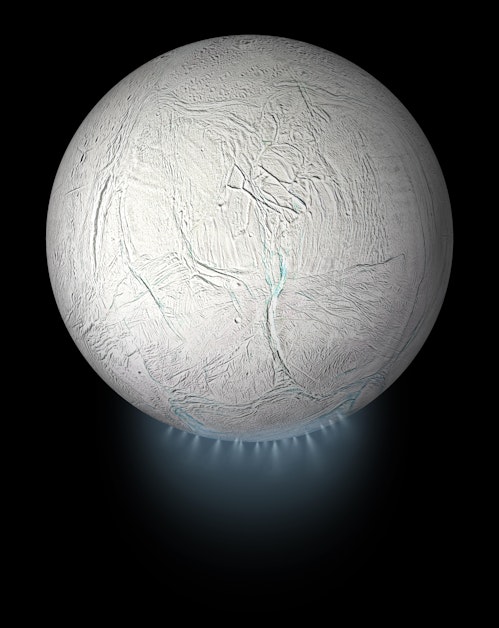

The small moon called — named after the giant in Greek mythology by the same name — doesn’t look like much. It’s a ball of monochromatic ice measuring about 500 kilometers in diameter, about as wide as Arizona; in contrast, Earth is more than 12,000 kilometers in diameter. But beneath its icy crust, there lies an ocean. And it’s that ocean that has scientists so enamored with Enceladus.

“If you look at Earth, everywhere there is water, there is life,” said Fabian Klenner, a postdoctoral scholar in Earth and space sciences at the University of Washington. “So, whenever we find liquid water beyond Earth, we are very curious to look for life there.”

There’s more to it than that, though.

Last year, Klenner was part of a team of scientists who on Enceladus. They found phosphates in ice samples collected by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft.

“There are a few elements that are very important for life as we know it, and that’s hydrogen, carbon, phosphorus, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen. And phosphorus is by far the least abundant in the universe,” Klenner explained. “Finding that in an ocean world is incredibly exciting.”

Before anyone starts to pack their bags for life on Enceladus (United Enceladus? Or perhaps Enceladusburgh?), KUOW’s Soundside asked the obvious question: Just how likely is it that there is life below this moon’s icy crust?

“That’s the $100 million question,” Klenner said. “We don’t know if there is life, but what we know is that there are the right ingredients.”

Here’s the thing: These phosphates indicate there could be life on Enceladus, but we don’t know whether there is life.

“Nobody has ever detected life beyond Earth,” Klenner said.

He posited that that could be because of the limitations of our earthly tools, the instruments we send into space to collect the samples scientists then test for the building blocks of life. They can detect something like phosphorous, but can they truly detect life, living organisms, on another planet?

Klenner said yes — and no.

“With current and future instrumentation … we are capable of finding bacterial cells,” he said, but those cells have to first make their way into the grains of ice that are collected by our instruments. It’s complicated.

Enceladus has Earth’s attention, though.

According to Klenner, NASA has said a mission to the icy moon is its second highest priority, just behind a mission to Uranus. Plus, Klenner said the its next big mission would go to Enceladus.

Meanwhile, back on Earth, Klenner and his colleagues will continue to analyze the data they have, looking for signs of life — whatever that may look life on an icy moon 790 million miles away.