Early-life trauma has the potential to alter the genetic development of the body’s pain response mechanism, creating a lasting pain “memory” that can influence how the body reacts to injuries later in life, as per a study published in Cell Reports by researchers from Cincinnati Children’s. Recent studies have highlighted the phenomenon of the human body retaining the memory of pain from infancy, including experiences like critical surgeries, well into adolescence.

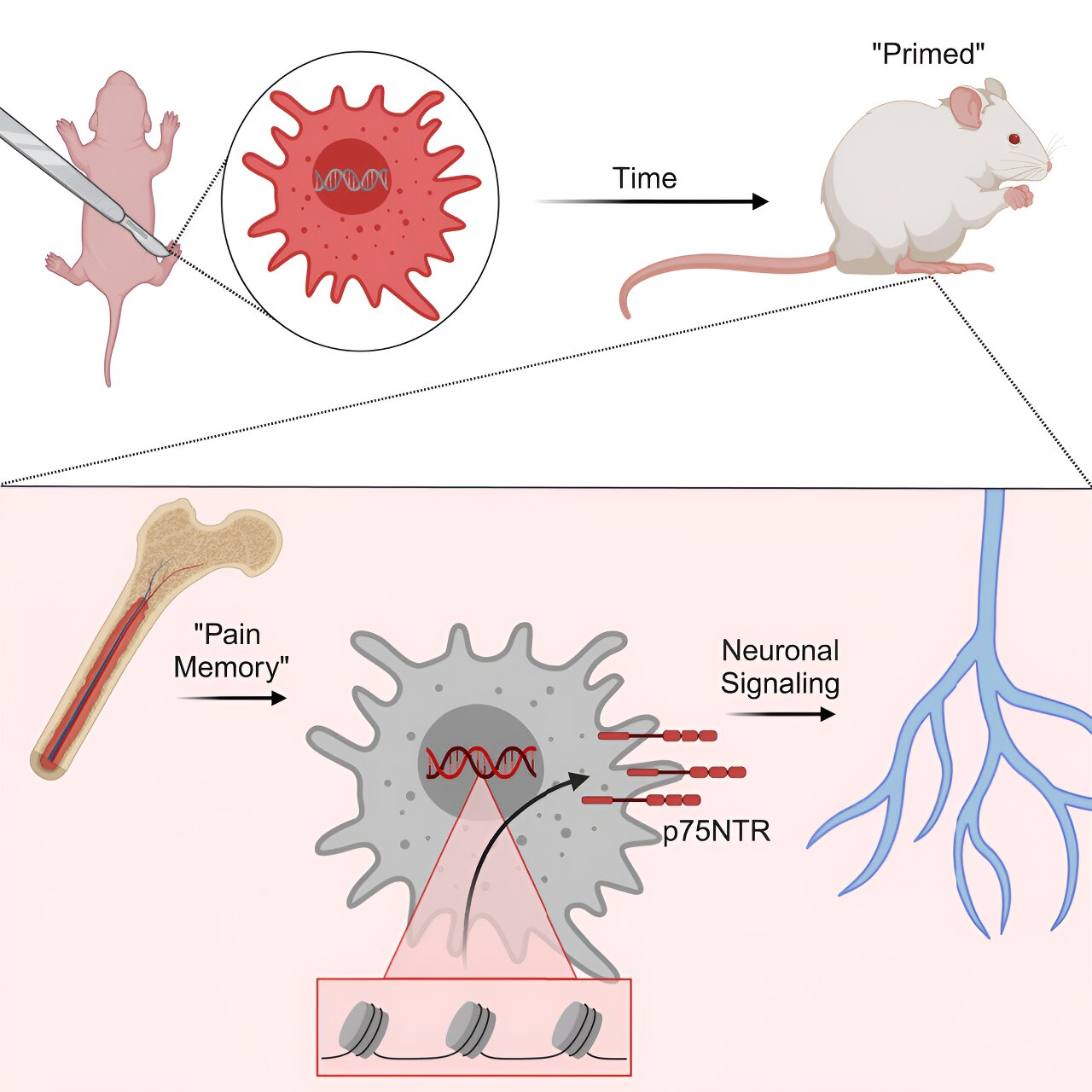

These early encounters seem to impact the genetic evolution of a child’s pain response system, leading to heightened sensitivity to pain in the future, with females being more susceptible to these changes. The latest research conducted by Cincinnati Children’s experts has identified the specific cells and processes responsible for the formation of this enduring pain memory. Published online on April 18, 2024, in the journal Cell Reports, the study reveals that significant alterations occur in developing macrophage cells, a crucial component of the immune system.

Dr. Michael Jankowski, the corresponding author and Associate Director of the Pediatric Pain Research Center at Cincinnati Children’s, explains that their experiments shed light on how pain memories impact newborn females over extended periods. The data suggests that following an early-life injury, an epigenetic modification occurs in macrophages, leading to heightened pain responses to subsequent injuries later in life, distinct from inherited gene variations.

Although male mice subjected to similar early-life injuries exhibit the same epigenetic changes, they do not retain the same long-term pain memory observed in females. Further investigations revealed similar changes in a gene known as p75NTR within human macrophage cells.

In female mice, the effects of pain memory persisted for over 100 days post-injury, causing the generation of macrophages that were predisposed to heightened responses to injuries, thereby intensifying the experience of pain. In a human context, this timeframe would equate to approximately 10–15 years.

The researchers were surprised by the profound impact of a localized injury on the broader epigenetic and transcriptomic landscape of systemic macrophages. This newfound insight into neonatal pain memory underscores the fundamental disparities in genetic activity between a developing newborn immune system and that of adults, posing challenges in tailoring recovery care for newborn and infant girls.

Dr. Jankowski emphasizes the need for more targeted treatments to prevent the reprogramming of immune responses in light of these findings, suggesting that a mere adjustment in pain medication doses may not suffice. The study’s next steps involve leveraging this knowledge to devise therapies that can effectively manage immune “pain memories.”

While blocking the p75NTR receptor in young mice showed promise in mitigating prolonged pain-like behaviors by impeding macrophage communication with sensory neurons, the safety and efficacy of such approaches in targeting human macrophages remain uncertain. Dr. Jankowski highlights the potential of emerging technologies to selectively block the p75NTR receptor in macrophages but underscores the necessity for extensive research before clinical trials in humans can be considered.

The study’s co-authors from Cincinnati Children’s span various departments, including Anesthesia, Bioinformatics, Experimental Hematology and Cancer Biology, Infectious Diseases, and the Center for Autoimmune Genomics and Etiology. The research findings, as detailed in the study published in Cell Reports in 2024, offer valuable insights into the enduring impact of early-life pain experiences on the immune system.

For more information, refer to the publication:

Adam J. Dourson et al, Macrophage memories of early-life injury drive neonatal nociceptive priming, Cell Reports (2024).

Citation:

Immune cells carry a long-lasting ‘memory’ of early-life pain (2024, April 18) retrieved 18 April 2024 from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-04-immune-cells-memory-early-life.html