The Life-Saving Function of the Iron Lung

Paul Alexander, who recently passed away at the age of 78, relied on the iron lung for over 70 years after polio left him completely paralyzed in childhood. Developed in the 1920s, this remarkable device enabled him to breathe by mechanically simulating the respiratory process. Lying on his back, encased from the neck down in a metal cylinder, the iron lung created a vacuum to expand and contract his lungs, essentially breathing for him when his muscles could not.

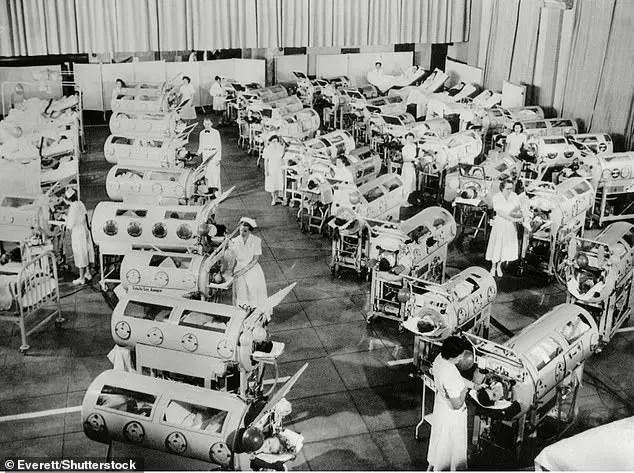

Advances and Adaptations in Polio Treatment

The iron lung was pivotal during the polio epidemics of the mid-20th century, particularly after its first successful use in 1928 at Boston Children’s Hospital. At the height of its use, thousands of these devices provided a lifeline in U.S. and UK polio wards. Though initially intended for temporary use during acute illness phases, innovations and the dire need led some, like Mr. Alexander, to depend on them long-term. Remarkably, he adapted a technique known as “frog-breathing” to manage short periods outside the iron lung.