David Schickele’s 1971 film Bushman begins in enigmatic fashion. We’re greeted by sounds of a dog barking, trees swaying in the wind, melodious and soothing bird sounds. Without any visuals to frame our imagination, the Iowa-born filmmaker immediately transports us to a rural, dreamlike landscape. We are then introduced to our protagonist Gabriel, played by Paul Okpokam, a young Black man photographed in resplendent black and white. He walks barefoot in a desolate section of an unidentified city, his shoes masterfully balancing on his head. As Gabriel observes the city, the camera, restless, follows him – the visuals reminiscent of the cinéma vérité style of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960) and John Cassavetes’ Shadows (1958).

The opening title card illuminates the world further: the year is 1968, and Martin Luther King, Robert Kennedy and Bobby Hutton (a Black Panther killed by Oakland police) are among the recent dead. We also discover that in Nigeria, the civil war is entering its second year. A tribal chant in Igbo (the ethnic language of southeastern Nigeria) subtly builds as Schickele takes us to Nigeria where we see a young boy and girl walking barefoot, a yam balanced on their heads. They are surrounded by woodlands as they hurriedly navigate their familiar terrain.

In these opening seconds a vision of rural life is potently juxtaposed against an urban one. We see two cultures at an important moment in history. Schickele uses Gabriel to interrogate the cultural and political climate of this tumultuous period. We learn that Gabriel has recently travelled from Nigeria to America to study and eventually teach at San Francisco State College.

Through a series of intimate conversations with Gabriel, we are transported to his life in Nigeria. Bushman is a complex and compelling snapshot of his past, present and uncertain future. Erudite and articulate, he addresses the camera: “At night, we sit around the log fire, listening to folktales…” Through photographs of a young Gabriel and luminous snapshots of village life, we are transported to his memory and recollections of a home informed by religion, ancient traditions and community.

Gabriel is a complex and multifaceted character: a man plagued by secrets from his past, his life drastically altered by the devastating impact of Nigeria’s civil war. At 27, he leaves his homeland for new pastures.

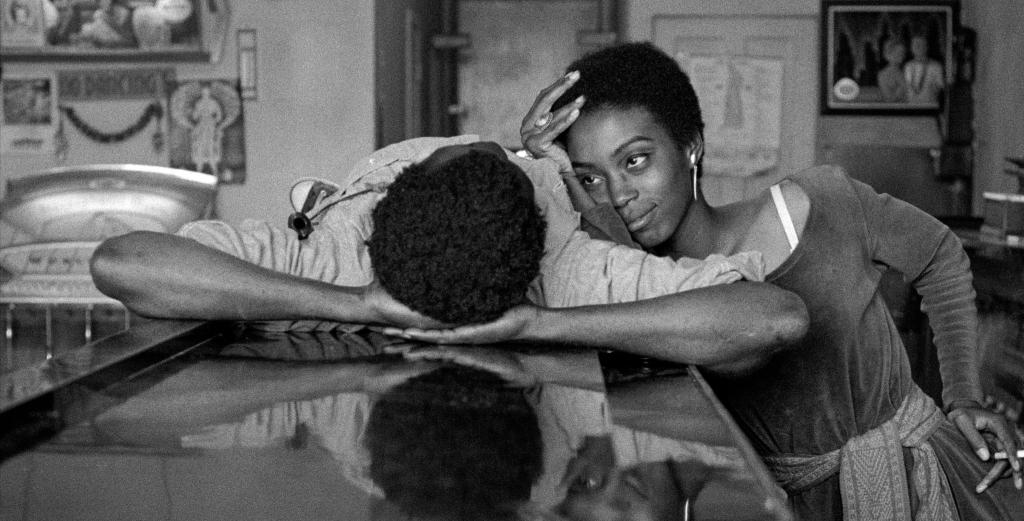

In San Francisco, he is forced to navigate his new environment as an outsider. He is fetishised, stereotyped and othered: “Why don’t you say something in African for me?” “You ain’t one of ours, where did you come from?” – Gabriel’s cultural traditions and way of life are interrogated by the lovers and strangers he meets on his adventures in the land of the ‘free’. In one of his intimate interview-style monologues, Gabriel tells us: “A traveller is like a ghost, he keeps going, crosses the rivers, passes through darkness, flies with the birds, until he comes to a land where nobody knows him.” This profound and poetic expression of Gabriel’s journey is emblematic of the shared immigrant experience – one that I can deeply relate to as a British-Nigerian man.

Maya Angelou, the memoirist and poet, once wrote: “The ache for home lives in all of us, the safe place where we can go as we are and not be questioned.” This vision of home tragically eludes our hero – a point which is further anchored by a shift in the film’s tone and form. The director abruptly interrupts his own work to announce, via voiceover, that the actor playing Gabriel has been falsely accused of terrorism and has subsequently been imprisoned. What began as a fictional tale evolves into an extraordinary exploration of real events. The star becomes the subject. Gabriel might be a ghost, but Paul is unable to escape life’s harsh realities. His fate is inexplicably tied to the systematic prejudice of his time.

While most filmmakers might have abandoned the project all together at this point, Schickele is committed to authentically capturing truth on screen. His early filmography is proof of this fierce devotion to realism. Give Me a Riddle (1966), the hour-long documentary which he produced and directed for the Peace Corps while he was working as a volunteer for them at the University of Nigeria at Nsukka, captures the bloom and buoyancy of Nigeria’s youth at a pivotal point in the country’s history. It was on Give Me a Riddle that he met and formed a life-long friendship with Okpokam, who features prominently in the documentary and who would become Bushman’s persecuted lead.

Made with a seed grant from the American Film Institute, Bushman was Schickele’s second feature and played at New Directors/New Films and the Chicago International Film Festival, where it was nominated for best feature. Following its festival run, however, it was never formally released and has since developed a cult status as a stylish and striking embodiment of 1970s American independent cinema.

Revisited today in the new restoration, the audacity and singularity of Schickele’s vision reflects a rare cinematic voice and sensibility. Bushman is revealed as a work of extraordinary depth, power and beauty. Subverting cinematic form and defying convention, it’s an urgent and poignant exploration of our shared humanity.