Two research laboratories, renowned for their groundbreaking innovations in the tech industry, have united with the aspiration of reviving their former glory days.

This tale is deeply ingrained in the lore of Silicon Valley.

Back in 1979, a youthful 24-year-old Steve Jobs was granted access to Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) to witness a demonstration of an experimental personal computer known as the Alto. Jobs departed with a handful of concepts that would revolutionize the realm of computing, eventually forming the core of Apple’s Lisa and Macintosh computers.

Upon witnessing the Alto’s graphical user interface, Jobs remarked, “it was evident to me that all computers would operate in this manner someday.” SRI

Fast forward four decades, and PARC has somewhat faded into obscurity within the technological hub of Silicon Valley, despite the valley’s burgeoning influence. Last April, Xerox discreetly transferred ownership of the lab to SRI International, an independent research institute that operates as a nonprofit organization with a rich history that has also experienced a decline from its pinnacle of prominence. (The institution rebranded itself this year to SRI, previously known as the Stanford Research Institute post its separation from the university in 1970, and later adopting the name SRI International in 1977.)

PARC’s innovations have been instrumental in shaping the personal computing revolution, from laser printing to ethernet.

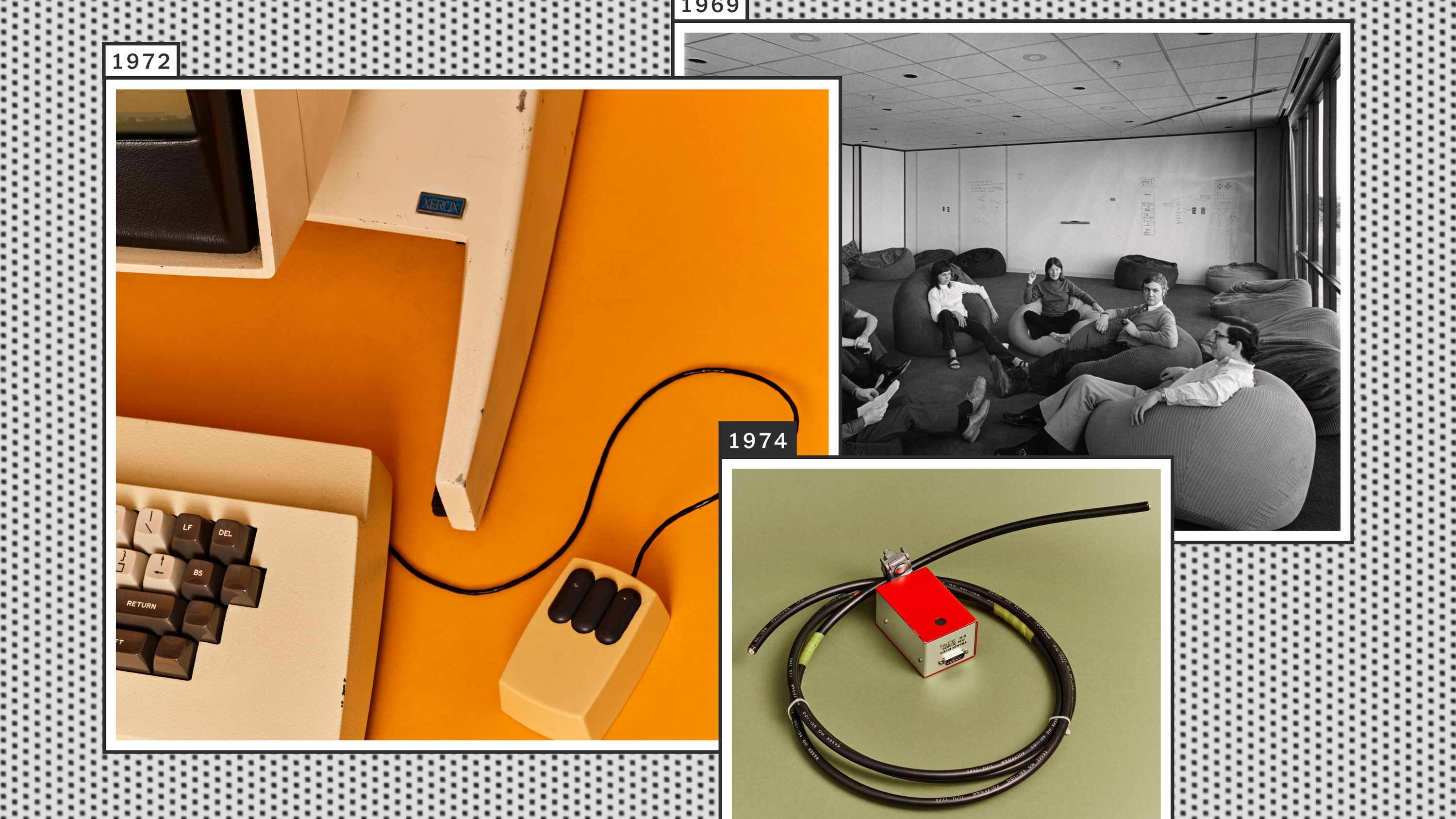

1969

Xerox establishes the Palo Alto Research Center as an R&D division on the outskirts of Stanford’s campus. The lab’s mission is to envision and create “the office of the future.”

SRI, via Computer History Museum

1972

One of the initial breakthroughs to emerge from PARC is a comprehensive system for laser printing, exemplified by a prototype printer model, the Xerox Dover.

1973

PARC introduces the Xerox Alto, a pioneering modern personal computer featuring the first graphical user interface, enabling users to interact with the system through intuitive pointing and clicking on menus rather than laborious command inputs.

1974

Integral to PARC’s vision of the future office is a network to interconnect office systems. The Ethernet standard, developed at PARC, garners widespread industry adoption over time.

In January, SRI unveiled its strategy for PARC, outlining a collaborative nonprofit research entity named the Future Concepts division, aimed at recapturing the innovative spirit that characterized the early days when Xerox Corporation embarked on establishing a fundamental research laboratory to pioneer the “office of the future” in 1970.

Situated in the foothills south of Stanford, the PARC facility now stands largely vacant, accommodating fewer than 100 researchers, a far cry from its peak workforce of nearly 400. Nevertheless, for those who reminisce about its golden era, it serves as a testament to the research conducted by a diverse cohort of scientists and engineers who transcended disciplinary boundaries and fostered collaboration akin to other renowned corporate research hubs of that era, such as AT&T’s Bell Laboratories and IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Center.

Despite Silicon Valley’s expanding influence, PARC has somewhat receded into the background.

“It retains its magical allure,” reminisced Eric Schmidt, the former chief executive and executive chairman of Google, who commenced his career at PARC as a computer scientist and research team member. He fondly recalls “an extraordinary cafeteria, breathtaking views from the roof deck overlooking the Bay Area, and expansive ground-floor labs once dedicated to physics and semiconductor research.”

In the contemporary landscape characterized by stringent corporate budgets and targeted government funding, fundamental research predominantly thrives within academic institutions. Silicon Valley has embraced a venture capital-driven research funding model focused on expedited product development — often resulting in swift failures.

From the fiercely competitive realm of computing research to the exorbitant living costs in the surrounding communities, skepticism abounds regarding the prospect of a revitalized PARC. In a technology ecosystem now dominated by venture-backed startups, some argue that fundamental research laboratories like PARC and SRI have become outdated.

“PARC is a relic of the past,” remarked Bernardo Huberman, a physicist who was a PARC researcher in the 1970s and 1980s and currently leads a research group at CableLabs, a research organization supported by the cable television industry. He emphasized that “the ethos that once engendered a sense of intellectual belonging at PARC has dissipated.”

“The current culture is more transactional, fixated on financial gains rather than the pursuit of knowledge for its intrinsic value,” Huberman added.

PARC and SRI share a complex legacy. During the nascent years of Silicon Valley in the 1960s and ‘70s, SRI, situated in neighboring Menlo Park, and PARC conceived seminal concepts that continue to shape the computer industry, encompassing advanced chip design, personal computing, laser printing, office networking, and the foundation of the Internet of Things.

Some of PARC’s computing innovations trace back to prior research endeavors at SRI under the tutelage of Douglas Engelbart, the computer scientist credited with inventing the computer mouse and hypertext, a precursor to the World Wide Web.

Throughout its 78-year journey, SRI’s innovations have evolved from early computer-based check processing systems to the embryonic version of Siri.

1950

Bank of America enlists SRI to devise a computer-based system for automating check processing. By 1966, the Electronic Recording Machine, Accounting can handle 750 million checks annually.

1966

A robot named Shakey navigates its surroundings, paving the way for advancements in computer vision, voice recognition, and an algorithm foundational to modern navigation and mapping programs.

1968

Douglas Engelbart showcases the “oN-Line system,” developed by his SRI team, in a live demonstration, unveiling the computer mouse and hypertext — the precursor to the World Wide Web.

1969

Two young programmers, Bill Duvall at SRI in Menlo Park and Charley Kline at UCLA in Los Angeles, experiment with remote computer access via the Pentagon-funded ARPAnet.

2003

Siri, later commercialized by Apple, originates from a Pentagon-funded SRI artificial intelligence initiative known as CALO (Cognitive Assistant That Learns and Organizes).

David Parekh, SRI’s CEO, acknowledged the challenges in competing for talent against tech behemoths offering lucrative salaries. Nonetheless, he expressed confidence in attracting researchers intrigued by the research autonomy afforded by the laboratory. The amalgamated lab is poised to host approximately 1,000 researchers.

Parekh, a mechanical engineer with a background in the aerospace industry who assumed the role of SRI’s CEO in 2021, asserted that while the revamped PARC may not embody a singular vision akin to “inventing the office of the future,” it aims to make strides across diverse domains, ranging from material science innovations addressing climate change to advancements in quantum computing.

PARC is acclaimed for pioneering the WIMP interface, the original graphical computing breakthrough denoting Windows, Icons, Menus, Pointer — a human-computer interaction style popularized by Macintosh and Windows PCs.

Parekh envisaged a paradigm shift in human-computer interaction, building on foundational research conducted at SRI in the 2000s that led to the commercialization of SIRI, a speech assistant integrated into the iPhone by Steve Jobs shortly before his passing in 2011.

He expressed optimism about the new research center’s potential to drive significant advancements in developing more trustworthy and explicable artificial intelligence systems. SRI has been at the vanguard of A.I. research since the 1960s, and Parekh highlighted the synergy between contemporary neural net technologies and traditional symbolic A.I. approaches, propelling the emergence of robust reasoning systems.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is currently backing PARC’s research on futuristic human-machine collaboration, aimed at facilitating seamless planning and collaboration between humans and machines in both digital and physical realms.

The pivotal challenge, as outlined by Curtis Carlson, a physicist who served as SRI’s CEO from 1998 to 2014, lies in fostering a culture that bridges the gap between invention and innovation — translating inventions into market-ready solutions with sustainable business models.

PARC’s inventive prowess has always sparked debate. Xerox faced criticism for “missing the boat” by failing to commercialize the technology it pioneered to establish a significant foothold in the computer industry. Jobs assimilated the technology that continues to define Apple’s products, while Charles Simonyi, a former PARC software designer who joined Microsoft, leveraged ideas that shaped both Office and Windows.

Xerox executives countered the critiques by underscoring the substantial returns garnered from commercializing PARC’s laser printer technology.

However, many researchers who witnessed PARC’s formative years emphasized that the lab’s strength lay in the freedom to pursue unconstrained research without the pressure to deliver a specific product — a concept seemingly inconceivable in today’s product-centric Silicon Valley.

During the 1970s, PARC was colloquially dubbed “hippie-ville,” recalled Jan Vandenbrande, a former Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency project manager who now spearheads research at PARC. While the culture has evolved over time, it has retained a spirit of “making a meaningful impact on the world” and “democratizing certain technologies.”

Johan De Kleer, a veteran scientist at PARC for nearly four decades before departing to establish an A.I. software company, suggested that PARC’s revival hinges on creating room for open-ended research projects, characterized by flexibility and support for unconventional ideas.

SRI appears to have found that flexibility. Nestled in Menlo Park, California, the research lab’s strategic location within walking distance of the San Francisco to San Jose commuter rail line on 63 prime acres in Silicon Valley positions it advantageously.

Parekh is now orchestrating the development of a contemporary research campus and residential community, featuring new SRI facilities and spaces designed to attract other high-tech enterprises. The revenue generated from this project will be shared with SRI, serving as an investment for future research endeavors.

“This initiative serves as our long-term investment in research,” articulated Parekh.