Planetary scientists have long speculated about the potential habitability of Venus, not at its hot surface, but in the cloud layers located at 48-60 km altitudes, where temperatures match those found on Earth’s surface. However, the prevailing belief has been that the Venusian clouds cannot support life due to the cloud chemical composition of concentrated sulfuric acid — a highly aggressive solvent. In a new study, chemists studied 20 biogenic amino acids at the range of Venus’ cloud sulfuric acid concentrations and temperatures. The researchers found 19 of the biogenic amino acids they tested are either unreactive or chemically modified in the side chain only, after 4 weeks. Their major finding is that the amino acid backbone remains intact in concentrated sulfuric acid.

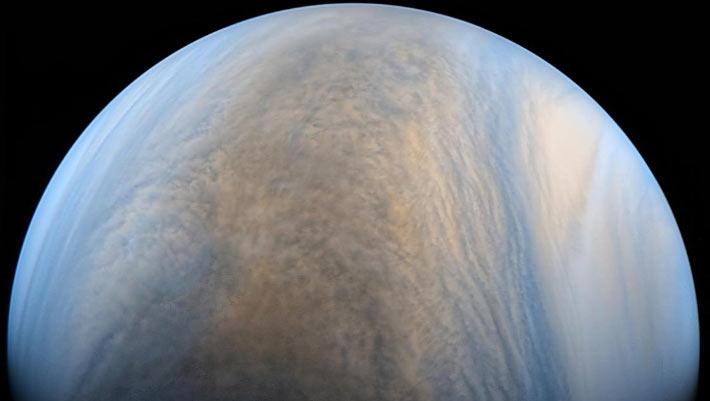

This composite image, taken by JAXA’s Akatsuki spacecraft, shows Venus. Image credit: JAXA / ISAS / DARTS / Damia Bouic.

“What is absolutely surprising is that concentrated sulfuric acid is not a solvent that is universally hostile to organic chemistry,” said Dr. Janusz Petkowski, a researcher at MIT.

“We are finding that building blocks of life on Earth are stable in sulfuric acid, and this is very intriguing for the idea of the possibility of life on Venus,” added MIT Professor Sara Seager.

“It doesn’t mean that life there will be the same as here. In fact, we know it can’t be. But this work advances the notion that Venus’ clouds could support complex chemicals needed for life.”

The search for life in Venus’ clouds has gained momentum in recent years, spurred in part by a of — a molecule that is considered to be one signature of life — in the planet’s atmosphere.

While that detection remains under debate, the news has reinvigorated an old question: Could Earth’s sister planet actually host life?

In search of an answer, scientists are planning several missions to Venus, including the first largely privately funded mission to the planet, backed by California-based launch company Rocket Lab.

That mission, on which Professor Seager is the science principal investigator, aims to send a spacecraft through the planet’s clouds to analyze their chemistry for signs of organic molecules.

Ahead of the mission’s January 2025 launch, Professor Seager and her colleagues have been testing various molecules in concentrated sulfuric acid to see what fragments of life on Earth might also be stable in Venus’ clouds, which are estimated to be orders of magnitude more acidic than the most acidic places on Earth.

“People have this perception that concentrated sulfuric acid is an extremely aggressive solvent that will chop everything to pieces. But we are finding this is not necessarily true,” Dr. Petkowski said.

In fact, the authors have previously shown that complex organic molecules such as some fatty acids and nucleic acids remain surprisingly stable in sulfuric acid.

They are careful to emphasize, as they do in their current paper, that complex organic chemistry is of course not life, but there is no life without it.

In other words, if certain molecules can persist in sulfuric acid, then perhaps the highly acidic clouds of Venus are habitable, if not necessarily inhabited.

In the new study, the researchers turned their focus on 20 biogenic amino acids — those amino acids that are essential to all life on Earth.

They dissolved each type of amino acid in vials of sulfuric acid mixed with water, at concentrations of 81 and 98%, which represent the range that exists in Venus’ clouds.

They then used the nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer to analyze the structure of amino acids in sulfuric acid.

After analyzing each vial several times over four weeks, they found that the basic molecular structure, or ‘backbone’ in 19 of the 20 amino acids remained stable and unchanged, even in highly acidic conditions.

“Just showing that this backbone is stable in sulfuric acid doesn’t mean there is life on Venus,” said Dr. Maxwell Seager, a researcher at Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

“But if we had shown that this backbone was compromised, then there would be no chance of life as we know it.”